Leaving the 20th Century: Manic Street Preachers and the Death of a Party

Gordon Anderson takes us on a musical tour of the last days of the 20th century in Wales.

Gordon Anderson takes us on a musical tour of the last days of the 20th century in Wales, via the Manic Street Preachers’ 1998 album This Is My Truth Tell Me Yours and asks what is says about a country on the brink of devolution.

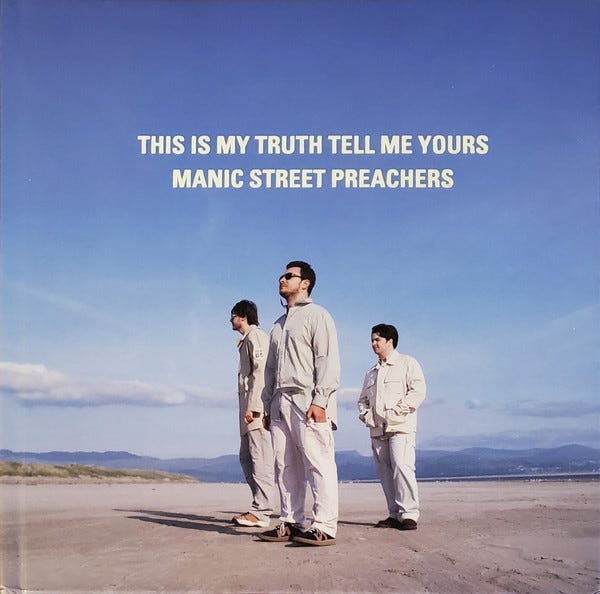

26 years ago, a three-piece group from Wales released an album. It sold five million copies.

Wait a moment. Five million copies? For comparison, there are three million people in Wales - enough for everyone to have a copy. And for a while, everyone did. Its key single encompassed the brave volunteers of the International Brigades and their fight against General Franco's fascists in the Spanish Civil War, the writer's fears of his own gutless pacifism, and the no pasarán principles that continue to inform working class resistance across the globe. The single went to no.1 in the charts.

The following week's no.1 was Bootie Call by All Saints.

In definitive biography Everything (Virgin, 1999), author Simon Price notes that the band had become, at this point, quite literally household names. “Your mum had heard of them. Your brother bought their last album, thinking it was their first”. (Uncannily accurate, as this writer can confirm.) Manic Street Preachers, once a thrilling mess of politics and glam-punk aesthetics, all Revlon and revolution, were now mainstream entertainment. And the mood of this new, mega-selling compact disc, This Is My Truth Tell Me Yours, magicked into every home like custard creams and Coco Pops? Resignation. Sadness. A retreat into oneself. And for the first time in five albums, a discernible Welshness, one that felt like drizzle over the hills. This change in the weather was strangely reflective of the times.

When a nationwide movement ends – in this case Britpop, that colossal, permanently buzzing three years where guitar bands high on ambition seemed to take over the country itself - there is always a hangover, a vacuum, a sense of something unfulfilled, of loss. In the margins of the collective unconscious, a scrawl saying: where do we go from here? Bands such as Pulp would re-emerge with albums of a darker hue, bruised by their experiences, cheapened by the shallow pleasures of fame (and having listened to a lot of Scott Walker). A certain 'pre-millennial anxiety' swept stealthily in, with Radiohead at the forefront of the cerebral angst-rock pack. A nation reeled from the death of Princess Diana and Geri Halliwell leaving the Spice Girls.

The Manics had surfed that same, frothing mid-90s wave, and found themselves suddenly arena-friendly. But as their leopardprint-clad 'old fans' started to melt away, hopelessly outnumbered by Ben Shermans, there was a sense that despite their protestations, the band - still grieving the loss of Richey Edwards, their bandmate and friend - were not completely comfortable with where they found themselves. "The enemy for us was what we had become," Nicky Wire would say later, promoting 2001's Know Your Enemy, "what we had let ourselves become." Sonically, This Is My Truth has surprising depth; lushly produced with sitar, omnichord, Wurlitzer and melodica adding colour and texture barely hinted at on 1996's trebly, game-changing Everything Must Go. In the parlance of the times, it is neither a party record nor a comedown album – too heavy in tone, too odd, and still throwing one or two flabby punches.

The preoccupations with the passing of time and the band's own complicated history are front of centre from the off, baked all the way through opener The Everlasting. Their most direct lyric to date, it contrasts the early days of the band's career '”when our smiles were genuine”, with the resignation of the present, represented by the defeated, bitter couplet “I don't believe it any more / pathetic acts for a worthless cause'”. A peculiar choice of single, this sort of not-ungraceful, melancholy plodder would have been unthinkable during the high-tempo Britpop years. But the mood had changed, notably capitalised on by The Verve, who hit paydirt with 1997's Urban Hymns, somehow intuiting that we were ready for an overlong album of faux gravitas, shiny strings, and chugging, mid-paced ballads. And we actually were. Was it the drugs not working? Or had everyone simply grown up and bought a house?

Despite the chunky, anthemic If You Tolerate This Your Children Will Be Next becoming their first number 1 (their second and last would come days after the gig of their lives, at the turn of the Millennium), rock thrills are light on the ground as the band indulge in the slick production, bizarrely garnishing one song with a unexpected whistling solo. However all is redeemed by the glorious Black Dog On My Shoulder, a treatise on depression never so beautiful. Light of touch, pithy and sympathetic, as it bounds into a graceful, minute-long guitar-and-strings coda underpinned by Sean Moore's pitter-pattering drums, it feels like the sun coming out over those rain-soaked hillsides. For a few minutes they sound once again like the Best Band in the World, an accolade they would take for the second time at the 1999 BRIT Awards, beating compatriots Catatonia. But finding themselves now part of the status quo they had openly despised, Nicky Wire would later refer to the BRITs as “a pretty hollow night”. The chasm between their past and their future had grown deeper still.

Elsewhere, the organ-led Ready For Drowning hints musically at Chapel as much it references water, fitting in the flooding of Tryweryn and a Richard Burton sample into what Wire calls his look at the “mythology of Welsh self-destruction” and “Welsh insecurities”. Elegiac yet defiant, the same feelings of doubt and loss also resurface, James Dean Bradfield spitting out the final verse's last line, “what is there to believe in?”. A search for meaning, and one with no comfortable conclusions. It certainly seemed to reference matters beyond their own messy origins. Within just a few years, Britpop had burned brightly then died - bloated, used-up, its heroes riddled with ugly track-marks and ragged septums, many retreating to afternoons with the blinds drawn or to a very big house in the country. Some were back on the dole. The brief period of optimism, a genuine 'feelgood factor' that had somehow manifested itself alongside a loud, easy to access, extremely white, largely working class musical movement, the Euro 96 football tournament and the changing of the political guard, was gone. Blair was in. And in Wales, just 50.3% of the 50% who bothered to vote (a margin of 6,721 votes) said a timid and underwhelming 'yes?' to the country having its own National Assembly, to Wales having lawmaking powers for its own people. Where do we go from here?

The emergence into the mainstream of other Welsh bands and cultural figures in the mid-90s is well documented, and Richard King's fine oral history Brittle with Relics: A History of Wales 1962-1997 (Faber, 2022) interrogates the relationship between this and changes in the wider Welsh consciousness. How much this led to a sea-change in confidence within Wales can be debated, but the concentration of influence on the young in a time of five television channels cannot be overstated. For all but the loneliest hill farmer, it was impossible to avoid. Thousands of Welsh kids buying thousands of cheap electric guitars, bashing out chords, hoping to catch a glimpse of their new local heroes browsing the music shops of Cardiff, Newport and beyond. People you could be, surely, if you tried. This, without question, was new.

The greater shift in Wales since has been gradual. The slow assimilation into the consciousness that we might have some small power over our destinies. The English speaking populace becoming steadily more open to the Welsh language, the stories of longstanding, marginalised Black and Asian communities finally coming to the fore, the relative lack of surprise when a Welsh actor or musician receives recognition from the establishment. It was not always thus. The wider landscape has changed forever; music culture now less tribal, more open to new ideas, to cross-pollination, to sounds and languages that would have once been relegated to a horrid, indefinite cul-de-sac called 'world music'. Close to home, this new frontier has been explored by Welsh and Cornish-language artists such as Adwaith and Gwenno, the beauty and complexity of these languages now allowed national airtime beyond Radio Cymru or 11pm on the John Peel show.

Whilst it is easier than ever for a Welsh band to be heard in Manaus or Manila, it is arguably harder than ever to create a cultural movement within the UK; the internet's capacity for network building cancelled out by its inherent raft of distractions, and with the vast range of socio-political disagreements ripe for forest fires, constantly burning any new growth they might have stimulated. Music and the surrounding arts continue to reflect the culture, but crucially no longer generate the momentum to drive it. Hysteria is still possible, obsessive fandom positively encouraged, but with the volume of content constantly high, the tap always flowing full blast. The strange period of 'independent' music going 'overground', of upsetting the status quo, now seems quaint. Art no longer holds the cards, no longer disrupts, now just one of so many options in an endless menu.

With the party global, virtual and continual, there are no truly nationwide cultural movements to react against, to allow boom and bust, the hangover, the crash landing, the renewed search for meaning. The often entertaining yet serious criticism that once met the non-highbrow arts is reduced to rubble and ash. Bands in three hundred and sixty degrees, Sponsored Content, screens full of glare. And as they fade, the distorted reflection of your own face. Travel with us, for a moment, back to the opening minutes of this century, to the centre of Cardiff. As the last notes ring out at the Millennium Stadium and the huge New Year's crowd roar, the Manics start their way off stage close to 1am, Nicky Wire eventually smashing his bass to pieces after several entertainingly weak attempts. The band have peaked. Three working class Welshmen in their early thirties making history in a new, giant stadium that jumpstarts Cardiff's own zigzag jolt into the future.

It will be downhill for the band from here, if success is measured in sales, in enormodome tickets, in gold-painted discs. They will still be making records in two decades' time, some of these even good, as the memory of their old selves and their missing member transmutes into legend; a good story for a podcast, a documentary, another book. The ceiling of possibility for modern Welsh acts is raised for ever, only for the rules of the game to change. Any new band aiming for the stars now does so on 0.003 pence per stream and the hope of some vinyl and ticket sales, generating what momentum they can almost in isolation. A small nation battered by austerity, a pandemic and the Barnett formula may or may not be listening. But the future is unwritten and somewhere, as it always is, a page is waiting for a stain, for another truth, another question.

With thanks to Gareth Davies for his support in preparing this piece.